Every Catholic artist who wants to restore beauty in the Church will look to the past for inspiration. I think most will agree that the Church is living through a dry spell in terms of beauty, but we Western Catholics still have an extraordinarily rich artistic tradition. But it is also a diverse tradition, in the sense that there are many artistic eras and schools of thought that we might choose to study: Iconographic, Gothic, Renaissance, Baroque, and so on. What lessons should we take from them to use in our own age, and what is best left to the past? To answer this question, I would first like to address Renaissance Art, because I think it in particular has the potential to become a major pitfall for Catholic artists who might consider it as an ideal.

If the artist took the end of his art or the beauty of the work for the ultimate end of his operation and therefore for beatitude, he would be but an idolater.

Jacques Maritain, Art and Scholasticism

I once read a book by the professor Larry Shiner called The Invention of Art: A Cultural History. As I recall, this was the first time I discovered that the definition of “art” has changed dramatically since ancient & medieval times. The current definition, Dr. Shiner says, is a novelty. The idea that the artist’s role is to express himself in unique ways, or to make a contribution to art history, would have been completely alien to an ancient or medieval artist. This was because originally, at least in the Western heritage, an artist was basically the same thing as a craftsman. The painter and the ship-builder produced different works, but they were colleagues in the sense that their social role was to create things by the cleverness of their minds, hands, and tools of the trade. The painter was merely a craftsman who produced paintings, the sculptor was a craftsman who produced sculptures, and so on.

These artists got better at their crafts over the years. At a certain point, around Renaissance era, the painters and sculptors had virtually mastered their arts, and could produce works that seemed so magnificent that things could hardly be improved anymore. The artist “came into his own”, and for lack of a better phrase, started showing off. Artists became so good at producing artworks that art seemed to be worth pursing for its own sake. Painting was raised from its original status as a trade for humble men to something equal to the liberal arts. Thus the artist’s service to the economy, or to the Church, became almost a distraction from the real work, which was art for Art’s sake.

If we were to rank the greatest paintings of all time purely in terms of skill, I think we would have to admit that the very best were produced during this period, when artistic ability and the pride thereof was at an all-time high. And thank God for these works, because they bear witness to the nobility of man in a way that little else can. As Goethe said: “Without having seen the Sistine Chapel, one can form no appreciable idea of what one man is capable of achieving.”

But still, I am convinced that the young Catholic artist today, if he wants to restore beauty in Church and the world, needs to be very careful if he looks to this unmatched Renaissance era for inspiration. The first reason is a merely practical one: you have to walk before you can run, and the harsh truth is that it took centuries of artistic development to produce the Renaissance masters. That tradition is not much alive anymore, and to think we can produce anything close to Renaissance work without putting in multi-generational effort is just not realistic.

The second reason, though, is spiritual. While we may like to think that whoever pursues Beauty is guaranteed to find the Good as well, it is not as simple as that. Even if you succeed, you may end up too good for your own good. You might pursue art with such abandon that you end up, as Maritain says, an idolater. And that was the characteristic flaw in Renaissance painting: it was too good for its own good.

St John Henry Newman discusses this at length in The Idea of a University:

When Painting, for example, grows into the fulness of its function as a simply imitative art, it at once ceases to be a dependant on the Church. It has an end of its own, and that of earth: Nature is its pattern, and the object it pursues is the beauty of Nature, even till it becomes an ideal beauty, but a natural beauty still. It cannot imitate that beauty of Angels and Saints which it has never seen. At first, indeed, by outlines and emblems it shadowed out the Invisible, and its want of skill became the instrument of reverence and modesty; but as time went on and it attained its full dimensions as an art, it rather subjected Religion to its own ends than ministered to the ends of Religion, and in its long galleries and stately chambers, did but mingle adorable figures and sacred histories with a multitude of earthly, not to say unseemly forms, which the Art had created, borrowing withal a colouring and a character from that bad company. Not content with neutral ground for its development, it was attracted by the sublimity of divine subjects to ambitious and hazardous essays.

Newman understood that when the art of painting (for example) reaches a certain level, it will tend to bring everything down to its own level. That is: if the goal of painting, considered in itself, is to imitate material nature, then once this art is perfected, it will tend to reproduce “earthly forms” at the expense of spiritual forms. Hence the tendency of the Renaissance masters to borrow themes so frequently from pagan nature religions, in which every immaterial reality is thought to be embodied in an anthropomorphic god or demigod. You can’t paint Beauty itself using earthly forms, but Venus is another story.

Gothic artists didn’t have this problem as much, because their lack of purely imitative skill led them to focus on expressing things more symbolically, and the deep Christian piety in the average artist’s mind meant that there was no shortage of things to express. They developed the ability to use visual forms as a kind of picture-language for spiritual realities. Even in the High Gothic era, when craftsmen did eventually become skilled enough to produce more realistic forms, the habit of referring to spiritual realities had been built up so strongly that even their realistic works had this visual-linguistic quality. This harmony between symbolic expression and high artistic skill achieved by Gothic art is described by Emile Mâle in his book The Gothic Image:

At an an earlier period than with which we are dealing these signs and conventions were of real service to the artist. By their help he could supplement the inadequacy of his technique. It was obviously easier to draw a cruciform nimbus round the head of the Christ than to show in His face the stamp of divinity. In the thirteenth century art could have done without such assistance. The artists at Amiens who clothed with so great majesty the Christ teaching at the door of their cathedral had no need of it … But faithful to the past the thirteenth century did not relinquish the old conventions, and deviated little from tradition. By that time the canons of religious art had grown to have almost the weight of articles of faith, and we find theologians consecrating the work of the craftsmen by their authority.

To illustrate how Gothic art maintained its inner logic even as its skill improved, consider two Gothic images of Jesus Christ, the first from a stained-glass window at Chartres Cathedral, and the other a sculpture at Amiens Cathedral.

Notice that in the first image, Christ is shown to be divine by the nimbus symbol around his head. But in the second image, the artist is so skillful that he has made Christ’s face itself seem to communicate divinity. And yet in both artworks, the symbolic language remains. In the more realistic sculpture from Amiens, Christ still blesses us with the exact same gesture as he does in the stained glass from Chartres, and he still proclaims himself as fullness of divine revelation in a symbolic way, by holding the Scriptures. They symbolic theme still dominates both images, such that our minds are directed towards the spirit realm when we look at them.

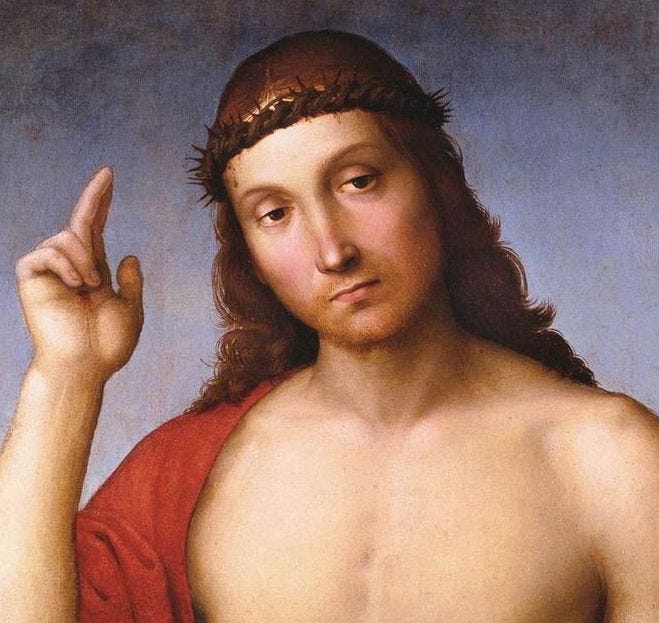

Now, compare these works to a similar one from the Renaissance Master Raphael, which is simultaneously much more skillful in its realism, and at the same time poorer in its spiritual communication.

It’s a marvel of in terms of painting ability, but what is it worth in the spiritual sense? Judging by appearances, it looks like Raphael was using a model here, that he had him pose in a way that he imagined Christ might have stood, and then reproduced what he saw as realistically and cleverly as possible. He succeeded in doing that, but I think he succeeded too much. For example, we can see that Raphael has accurately captured his model’s bored expression and stubble. By imitating nature too exactly, Raphael has brought details into the image that distract us from heaven.

When I look at the earlier Gothic images, there is no doubt that I am thinking about Christ the God-man. When I look at Raphael’s work, I marvel at his abilities, but I still can’t help but feel that I am looking at the image of a mere man. At this point, painting as an imitative art has come too far, and it is trapped in “earthly forms”. The artwork no longer serves as an intermediary between two worlds. It is an excellent manifestation of this world, but it is also stuck in this world.

But why stop at Gothic art? Are there no other art forms in our tradition besides the Gothic that are viable alternatives to the Renaissance? The Iconographic tradition seems to suggest itself pretty strongly. That tradition is no doubt a marvelous one, and I consider it to be a living treasure of the Church which I hope never dies. However, I am trying to answer a question about Western art, and it seems clear to me that Iconography has become the special patrimony of the Eastern churches. At this point in history, I think it would take a great cultural shift in the West before we could make that patrimony truly our own. Assuming I’m right, that leaves us with one more major consideration: the Baroque Era.

Baroque art, which follows the Renaissance, has many different aspects and modes of expression. In its best form it is based on the reform of the Church set in motion by the Council of Trent. In line with the tradition of the West, the Council again emphasized the didactic and pedagogical character of art, but, as a fresh start toward interior renewal, it led once more to a new kind of seeing that comes from and returns within. The altarpiece is like a window through which the world of God comes out to us. The curtain of temporality is raised, and we are allowed a glimpse into the inner life of the world of God. This art is intended to insert us into the liturgy of heaven.

Joseph Cardinal Ratzinger, The Spirit of the Liturgy

The Baroque Era was, I think, a great artistic achievement that managed to wield just as much technical skill as the Renaissance masters did, while still managing to effectively communicate spiritual realities symbolically, like the Gothic artists did. In that sense, it is the best of both worlds. As Christopher Dawson wrote: “It was as though the Gothic spirit was expressing itself anew in classical forms.” If the Renaissance represents the highest ideal in terms of human artistic skill, and if the Gothic Era represents the ideal in terms of the ability to represent heavenly realities in visual forms, then the Baroque Era will surpass both traditions to the degree it succeeds in synthesizing them. This is evident, for example, in Bernini’s Cathedra Petri in St Peter’s Basilica, in which earthly forms and heavenly symbols coexist in luminous harmony.

What traditional Catholic wouldn’t want to see more of this? Still, it’s a long road to get there. It is no small task to achieve this level of technical skill, and many don’t have sufficient leisure to learn. What’s more, if we want liturgical art to ever reach this level again, we will also need to recover the “Gothic spirit” again, which means the development (or restoration) of the rigorous picture-language that can be used to express spiritual realities. Likewise, we would also need to recover a strong acquaintance with those spiritual realities that we wish to express, which is done through prayer.

Also, I think it’s important to point out that even if we do manage to reach such lofty goals, it wouldn’t necessarily resurrect the Baroque era. We are cut from a different cloth nowadays (culturally speaking), and and we are also fighting a different battle than the Baroque artists were. They were primarily concerned with Protestantism, but we are faced with an army of anti-Christian ideologies: nihilism, atheism, scientism, and even the return of nature-religions, just to name a few. The artistic forms that triumph over the enemies of our day will surely have their own unique character.

We are not living in an age of wealth and loyalty, of pomp and stateliness, of time-honoured establishments, of pilgrimage and penance, of hermitages and convents in the wild, and of fervent populations supplying the want of education by love, and apprehending in form and symbol what they cannot read in books. Our rules and our rubrics have been altered now to meet the times, and hence an obsolete discipline may be a present heresy.

St John Henry Newman, The Idea of a University

In the final analysis, none of the old Catholic art movements can be our goal as such. Art is at the service of the Church, and seeking to revive the Gothic or the Baroque style with too much fervor would distract Catholic artists from their true purpose, which is glorifying God through their work. We have so much to learn from our ancestors, but we should learn from them not in order to become more like them, but rather to regain the intellectual habits with which to meet the spiritual needs of our own age. The approach I recommend to aspiring artists—and the approach I use myself—is the following:

- To build the habit of illustrating spiritual realities through material forms and symbols, and to learn the symbolic language for spiritual things. For this purpose, I find that studying the art of the Gothic era is the most fruitful. Emile Mâle’s book on the subject is a great introduction. A familiarity with Scripture is also indispensable.

- To gain the technical skill to represent nature in a beautiful way, while avoiding the attendant dangers. Renaissance (and Academic) art are most instructive here, but today’s Catholics will need to be especially careful to avoid tainting their work with the paganism and immodesty that is often present in these schools. There are no perfect resources, but I find that learning the Russian Academic approach is an excellent starting place.

I think that if we can accomplish these two goals, we can then move on towards designing forms that can grab the attention of modern men and women, reminding them that there is a vertical dimension to this life, and that God is just as near to us as ever.

Leave a Reply