Here the fact that something looks so for man does not imply that the way it is, if we prescind from man’s mind, is the more authentic and more real, the more objectively valid. No, the appearance it offers to man belongs to its objective meaning, because God has created “this” world for man.

Dietrich Von Hildebrand, What is Philosophy?

The things around us can appear differently to us depending on the circumstances. A thunderstorm, for example, can appear beautiful if observed from a safe distance, so that the sound is dulled and the flashes of lightning can be perceived against the backdrop of a larger sky. Perceiving that same storm in the midst of it, perhaps on a boat, would produce an entirely different perception, that of the imposing and merciless power of nature. This raises an interesting question for aesthetics: which is it? Are storms beautiful or not?

The tendency, or perhaps the temptation, when faced with this dilemma is to conclude that it’s subjective, that a storm is not one way or the other in reality. But this conclusion is born from the failure to grasp the fact that we live in a world that was intentionally created. If we understand this at least in a rudimentary way, then things come into focus. God created this changing world for us, and therefore we expect that he also intends for it to appear to us in certain ways in different circumstances.

In his book What is Philosophy?, Hildebrand gives a helpful analogy for understanding this intentionality: the artist creating an image. The artist makes use of various visual devices to determine the way the things he paints will be perceived by the viewer. He might exaggerate shadows to produce an ominous feeling, or push certain colors to give a joyful and energetic impression. He might spend more time refining certain parts of the painting that he wants the viewer to focus on.

In doing so, he is not at all changing the nature or substance of what he’s depicting. On the contrary, if he is successful, he can bring out the nature of the subject better than even a photograph could. So, the artist is focused on the connection between the “objective” essence of the thing being painted and the viewer’s “subjective” cognizance of it. The subject remains what it is, or remains “objectively” what it is, if you like. But the good artist knows that the essence of his subject will only be “revealed” to the viewer if he invites the viewer to observe it under a certain aspect.

This idea was especially refined in Impressionist painting, where the impression on the viewer was so pronounced that it almost took the place of the painting’s subject in order of importance. In Impressionist painting, the artist chooses a subject, and tries to paint it in such a way that it will take on a special significance for the viewer, as if it were the viewer’s own memory of the subject. Just as a thunderstorm can give different messages depending on the circumstances, so too the Impressionist’s subject can send different messages to the viewer, depending on how the painter decides to paint it.

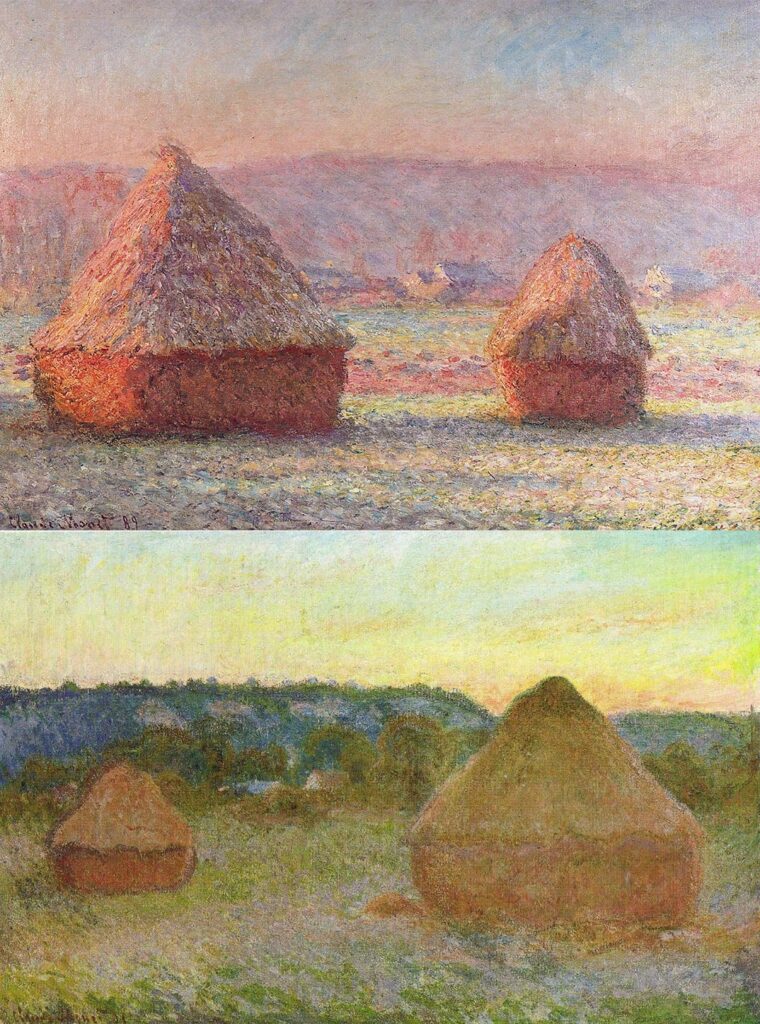

Monet’s Haystacks series is a good example. Monet took some stacks of hay in the French countryside as his subject, and painted them several times, and each time differently, availing himself of both various artistic techniques and the natural variations of time and season. He produced twenty-five of these paintings, and each one of them provides the viewer with its own distinct impression.

Now, I hope you’ll see that we can ask just the same question about these paintings that we asked earlier about the thunderstorm: which is it? Are haystacks in the French countryside meant to be viewed in the fading pink light of dusk, or in the tranquil yellow glow of dawn? Likewise, are they meant to invite us to a quiet reflection on the day that is passing away, or to a sense of wonder about the contingencies of the day ahead? Or is one of the other twenty-three impressions correct?

The answer is that they are all correct. I emphatically do not mean this in a subjectivist or relativist sense. It is not that viewer’s perception of the thing determines what the thing is. Rather, my claim is that the artist, if he is a good one, intends each painting to produce a certain impression on the viewer, and will succeed in doing so. And so the viewer, for his part, makes a correct judgment about the thing he’s viewing if he successfully receives the impression that the artist was trying to make.1 The artist can produce many paintings of the same subject, each under a different aspect which produces its own impression. The viewer, for his part, can receive all of these impressions. Taken together, they can give him a richer understanding of what the thing is, more so than if he had only a single aspect to go on.

Now consider God, the divine artist. He created the world intentionally, and his intention was to create it for us. Therefore we expect that this world was meant to be viewed by us under certain aspects and in certain states of mind. If we are to understand reality as it is, we must try to receive the impressions that God wants us to receive from creation. In doing so, we will understand what he is trying to tell us through the rich language of the created order.2

God, unlike the human artist, is a perfect creator, and so we cannot blame him for failing to produce the desired effect. Therefore, it falls on us to discover the aspects and the states of mind through which he wants us observe the world, and through which we can more accurately understand what he’s trying to tell us. Hildebrand, of course, puts it better than I can:

Here the fact that an appearance is meaningful, that it includes a significant contribution to the cosmos, and has a definite value—that fact permits us to consider it as a message from God, not in the sense of a direct word, but as the valid and authentic aspect of a real object … Message means here the God-given or God-willed aspect of an object of nature.

So we should not be scandalized by the fact that the natural world appears differently to us depending on the circumstances, any more than we should be scandalized that our photograph comes out wrong when the aperture or focus are poorly adjusted. Rather, we should take it as a challenge to discover the aspects from which God wants us to view his creation, so that we can understand him better through it.

- In reality, of course, there is often a failure in communication. The artist might desire an effect that is wrong, or he can lack the necessary skill to produce a right one. Likewise, the viewer might suffer from interior distractions that prevent him from receiving the impression. ↩︎

- Whether God intends us to view each created thing under one or many aspects is not a question that I intend to fully resolve in this essay. However, I suspect that it is many. Consider, for example, that we have four accounts of the Gospel instead of one. ↩︎

Leave a Reply