Art in General

In English, art is an ambiguous term, because it can refer to either a skill or a thing. When we say that there is an art of war, we are saying that art is a skill, namely the skill of fighting. But if we say we are looking at art, we are talking about object that is itself art, like a sculpture or statue.

I think that art most properly refers to a skill rather than a thing. This is evident from the fact that it is sometimes necessary for us, when we’re talking about art as a thing, to modify the word art to clarify what we mean. For example, artwork and artifact derive from art, but specify that we are talking about things, and not practices or skills. On the other hand, when we say something is a work of art, we reveal a latent assumption that the things proceed from the skill, and not the other way around, and therefore that art is primarily a skill or practice. So, going forward, let us use art in this limited sense, as a skill.

Practical Arts

Generally, arts are for some purpose: the art of war is for the sake of winning battles, the art of ship-building is for the sake of good ships, and the art of pottery is for the sake of pots. Notice too that each of these ends is for the sake of another end: winning battles secures peace for nations, building good ships allows for trade and exploration, and making pottery allows for the sanitary storage of food and drink. Such arts accomplish something for the sake of something else. We can call these practical arts.

Practical arts can be thought of as the “first arts”, insofar as they are the most immediately necessary arts for man to learn. Some of them can be essential for survival, like the arts of fire-making and archery. Many of them are necessary to produce a functional economy, such as textile arts and carpentry. They are the arts any society must cultivate in order to get off the ground. Their distinguishing feature is that they are practiced for the sake of producing something else, which can then be used in the ordinary course of life.

Fine Arts

However, the strange thing about art is that it can also be done for the sake of beauty, which does not necessarily imply purpose beyond itself. A good poet writes a beautiful poem, and it doesn’t need to be for the sake of honor or for anything else – he might just want to make it beautiful. A painter can paint a landscape, and it might not be for money or decoration – he might just want to represent the world in a beautiful way. In these cases, the artist has no purpose in mind beyond the thing that he makes, aside from making it beautiful. True, the art of painting properly speaking terminates in a painting, and not really beauty itself. But still, that painting is intended to be a manifestation of the elements of beauty.1 Its purpose, properly speaking, is to be beautiful and nothing else. We tend to refer to arts as fine arts when they are practiced in this way. As Jacques Maritain puts it in Art and Scholasticism:

In the fine arts the general end of art is beauty. But in their case the work-to-be-made is not a simple matter to be ordered to this end, like a clock one makes for the purpose of telling time or a boat one builds for the purpose of travelling on water. As an individual and original realization of beauty, the work which the artist is about to make is for him an end in itself: not the general end of his art, but the particular end which rules his present activity and in relation to which all the means must be ruled.

Sacred Arts

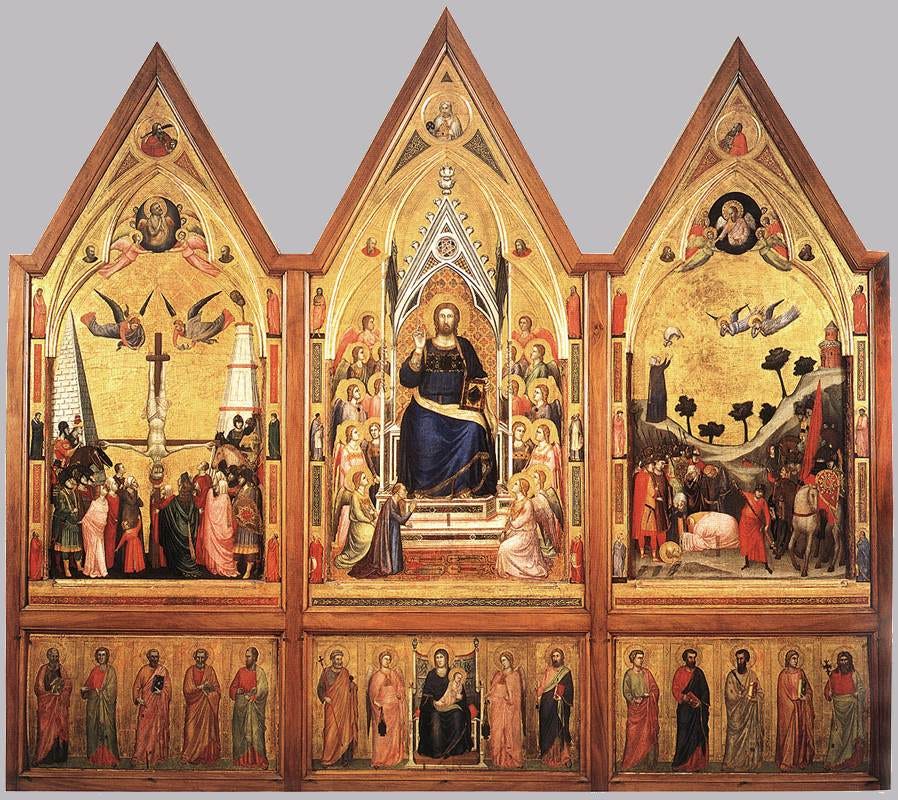

It is important in modern times, I think, to draw a clear distinction between fine art and sacred art, because in my view the two are often not carefully distinguished in the study of Art History. For example, when an art historian comments on a triptych, he must say something about its aesthetic value, but can get away with saying nothing of how well it does the job of adorning a liturgical altar.

This runs the risk of confusing students of Art History into thinking that sacred art is just another species of fine art. In reality, however, sacred art can be clearly distinguished as its own kind of art by virtue of its own distinct purpose: The aim of sacred art is to produce artwork that is fitting for use in religious rituals. Some obvious examples of this are chant, iconography and church architecture. Notice that these have much in common with practical arts, insofar as they serve a purpose beyond themselves—which in the Catholic context is generally the liturgy—but they also have much in common with the fine arts insofar as they are ultimately employed for an end-in-itself: God.

Parenthetically, it is an odd feature of modernity that there is a blurry line between sacred art and fine art. Alasdair Macintyre has traced this collapsed distinction between sacred art and fine art to the loss of distinction between the priestly and lay social classes in Protestant cultures:

When the Catholic mass becomes a genre available for concert performance by Protestants, when we listen to the scripture because of what Bach wrote rather than because of what St. Matthew wrote, then sacred texts are being preserved in a form in which the traditional links with belief have been broken, even in some measure for those who still count themselves believers. It is not of course that there is no link with belief; you cannot simply detach the music of Bach or even of Handel from the Christian religion. But a traditional distinction between the religious and the aesthetic has been blurred.2

It seems to me that in the West, the fine art tradition has grown from the much older and and more refined sacred art tradition. We can see this most clearly in a transitional figure like Leonardo Da Vinci, who began as a liturgical artist but in the end seems to have become more interested in art for its own sake.3 We might venture to say that in recent times the confusion between fine art and religious art has gotten so bad that the (so-called) fine artists have come to be perceived as almost pseudo-religious figures or pseudo-prophets.

Adornment

1. General Definition

There is also a strange category of art which we might call adornment. The most common example of this would be the decoration of a house, in which the things of everyday life are adorned with patterns, colors and images to imbue them with an agreeable and uplifting appearance. All kinds of things can be adorned, from faces to houses, to civic buildings and even churches. The subject of adornment is the whole of the human environment, excluding neither natural things nor human artifacts. Its aim is simply to make the immediate environment a more beautiful and pleasant place to be. It also stands “outside” of the other arts, in the sense that it can be superadded to the products of any human art, or even applied God’s own products (in the case of a garden, for example).

The art of adornment is sometimes held in contempt. It’s not unusual for someone to say something like “it doesn’t have to be pretty, as long as it works”. However, with the help of some philology, we can see that the Greeks thought of this art as noble, and even integral to the whole of creation. As Bishop Athanasius Shneider has said:

The whole of God’s created work is art, in Greek we say kosmos. The Greek verb corresponding to this noun also means “to adorn, to make beautiful”. That is why God made everything beautiful, as well as good and true, as Thomistic philosophy teaches us.4

While this verb, kosmein, could have masculine connotations in a military context, the art of adornment in the creative sense seems to have been closely associated with feminine beauty and taste, as it often is today. From the Etymological Dictionary:

The verb kosmein meant generally “to dispose, prepare,” but especially “to order and arrange (troops for battle), to set (an army) in array;” also “to establish (a government or regime);” “to deck, adorn, equip, dress” (especially of women). Thus kosmos had an important secondary sense of “ornaments of a woman’s dress, decoration” (compare kosmokomes “dressing the hair,” and cosmetic) as well as “the universe, the world.”5

At first it seems like a curious thing that a word like cosmetology could have developed from the same conceptual roots as the word cosmos, as if a lady getting ready is somehow integrally related to the whole of the created universe. But then again, we should remember a theological connection in this regard: that the one who is said to be God’s masterpiece is Mary, the woman adorned with grace more than any other creature, and that she is also called such names as Queen of the Universe and City of God. So there is a clear connection between adornment and cosmological significance in the Catholic context: they are connected in the person of Mary. But one might wonder how the Greeks came to notice it.

2. Adornment as “Minimal Art”

We have so far outlined the kinds of arts in order of nobility, with practical arts at the bottom, fine arts in the middle, and sacred arts at the top. We can tell the nobility of each kind by reference to the nobility of its respective purpose: 1. human needs (practical arts), 2. natural beauty (fine arts), and 3. the worship of God (sacred arts). We also said that the art of adornment stands somehow outside of this hierarchy, insofar as it can be applied to any of these three levels of art. What exactly is the relationship between adornment and the other arts?

The late Sir Roger Scruton has coined a term that I think is helpful in this investigation: minimal beauty. This is the kind of beauty that serves as the substrate, or background, of all the other beautiful things in the world. It’s the beauty that we discover in a clean room, in a dinner table setting, or in a tasteful suit of clothes. While minimal beauty might seem trivial at first glance, it is really very important, because it serves as an unassuming contrast against which the nobler beauties can manifest themselves:

Much that is said about beauty and its importance in our lives ignores the minimal beauty of an unpretentious street, a nice pair of shoes or a tasteful piece of wrapping paper, as though those things belonged to a different order of value from a church by Bramante or a Shakespeare sonnet. Yet these minimal beauties are far more important to our daily lives, and far more intricately involved in our own rational decisions, than the great works which (if we are lucky) occupy our leisure hours. They are part of the context in which we live our lives, and our desire for harmony, fittingness and civility is both expressed and confirmed in them. Moreover, the great works of architecture often depend for their beauty on the humble context that these lesser beauties provide.6

Adornment, it seems to me, is the art that is especially tasked with producing this minimal beauty. The practice of adornment will change a bit depending on the kind of thing that is to be adorned, but in any case the goal will be to provide the context or background against which the main thing can stand out. A clean room allows for the possibility of a light-hearted and engaging conversation. A nicely set table is the backdrop against which the chef’s art can be best appreciated. A well-designed street eases and prepares the mind of the walker as he approaches a great work of architecture, like a courthouse or a church.

Adornment is the art which assists in the preparation of all such things, taking objects and environments and making them especially appropriate for their purposes. It may look a bit different depending on what the main event is – that is, adorning a church with gilded motifs is very different from adorning a table with dinnerware. Nevertheless, in each case the goal is the same: to emphasize the main thing without distracting from it.

Perhaps we can put it this way: adornment makes use of any number of practical arts in order to provide a fitting environment for either fine art or sacred art, as the case may be.

- St Thomas identified them as integrity, proportionality and splendor, but of course there are other names for the elements: harmony, symmetry, fittingness, balance, etc. ↩︎

- See Chapter 4 in After Virtue. ↩︎

- “The first work which he here undertook was a design for an altar-piece for the chapel of the college of the Annunciati. Its subject was, our Saviour, with his mother, St. Ann, and St. John; but though this drawing is said to have rendered Leonardo very popular among his countrymen, to so great a degree, that numbers of people went to see it, it does not appear that any picture was painted from it … The picture, however, on which he bestowed the most time and labour, and which therefore seems intended by him as the completest specimen of his skill, at least in the branch of portrait-painting, was that which he did of Mona Lisa, better known by the appellation of la Gioconda, a Florentine lady, the wife of Francisco del Giocondo. It was painted for her husband, afterwards purchased by Francis the First, and was till lately to be seen in the King of France’s cabinet. Leonardo bestowed four entire years upon it, and after all is said to have left it unfinished.” (source) ↩︎

- See Chapter 5 of his book The Catholic Mass. ↩︎

- Taken from the Online Etymology Dictionary. ↩︎

- Taken from Chapter 1 of Scruton’s Beauty. ↩︎

Leave a Reply